By means of Jenny Graven /The conversation

Neanderthals, the closest relatives of modern humans, lived in parts of Europe and Asia until they became extinct about 30,000 years ago.

Genetic studies are revealing more and more about the ties between modern humans and these long-vanished relatives—most recently, a wave of interbreeding between our species occurred in the relatively short span of about 47,000 years ago. But one mystery still remains.

The Homo sapiens genome today contains a small amount of Neanderthal DNA. These genetic traces come from almost every part of the Neanderthal genome – except the Y sex chromosome, which is responsible for making males.

So what happened to the Neanderthal Y chromosome? It could have been lost accidentally, or through mating patterns or deteriorating function. The answer, however, may lie in an age-old theory about the health of interspecies hybrids.

Neanderthal gender, genes and chromosomes

Neanderthals and modern humans went their separate ways in Africa sometime between 550,000 and 765,000 years ago, when Neanderthals moved into Europe, but our ancestors stayed put. They wouldn’t meet again until H. sapiens migrated to Europe and Asia between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago.

Scientists have recovered copies of the complete male and female Neanderthal genomes, using DNA from well-preserved bones and teeth of Neanderthal individuals in Europe and Asia. Unsurprisingly, the Neanderthal genome was very similar to ours, with around 20,000 genes bundled into 23 chromosomes.

Like us, they had two copies of 22 of those chromosomes (one from each parent), as well as a pair of sex chromosomes. Females had two X chromosomes, while males had one X and one Y.

Y chromosomes are difficult to sequence because they contain a lot of repetitive “junk” DNA, so the Neanderthal Y genome has only been partially sequenced. However, the large portion that has been sequenced contains versions of several of the same genes that are in the modern human Y chromosome.

In modern humans, a Y chromosome gene called SRY starts the process of an XY embryo developing into a male. The SRY gene plays this role in all apes, so we assume it was true for Neanderthals as well – even though we haven’t found the Neanderthal SRY gene itself.

Neanderthals lived alongside modern humans in the Negev desert.Kovalenko I / Adobe Stock)

Interspecies mating left us Neanderthal genes

There are many small clues that indicate that a DNA sequence came from a Neanderthal or a H. sapiensSo we can look for bits of Neanderthal DNA in the genome of modern humans.

The genomes of all human lineages originating in Europe contain about 2% Neanderthal DNA sequences. Lineages from Asia and India contain even more, while lineages restricted to Africa have none. Some ancient Homo sapiens genomes contain even more – about 6% – so it appears that Neanderthal genes are gradually disappearing.

Most of this Neanderthal DNA arrived in a 7,000-year period, about 47,000 years ago, after modern humans came to Europe from Africa, and before Neanderthals went extinct about 30,000 years ago. During this time, there must have been a lot of mating between Neanderthals and humans.

At least half of the entire Neanderthal genome can be assembled from fragments found in the genomes of various modern humans. We have our Neanderthal ancestors to thank for traits such as red hair, arthritis, and resistance to certain diseases.

There is one notable exception: no modern humans have been found that possess any part of the Neanderthal Y chromosome.

What happened to the Neanderthal Y chromosome?

Was it just bad luck that the Neanderthal Y chromosome got lost? Was it not very good at its job of making men? Did Neanderthal women, but not men, engage in interspecies mating? Or was there something toxic about the Neanderthal Y chromosome that made it incompatible with human genes?

The AY chromosome comes at the end of the line if its carriers have no sons. So it may simply have been lost over thousands of generations.

Or maybe Neanderthal Y was never present in interspecies matings. Maybe it was always modern human males who fell in love with (or traded, grabbed, or raped) Neanderthal women? Sons born to these women would all have the H. sapiens shape of the Y chromosome. However, it is difficult to reconcile this idea with the finding that there is no trace of Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA (which is restricted to the female line) in modern humans.

Or maybe the Neanderthal’s Y chromosome just wasn’t as good at its job as its H. sapiens rival. Neanderthal populations were always small, so harmful mutations would have accumulated sooner.

We know that Y chromosomes carrying a particularly useful gene (for example for more, better or faster sperm) quickly replace other Y chromosomes in a population (the so-called hitchhiker effect).

We also know that the Y chromosome is generally lost in humans. It is even possible that SRY was lost from the Neanderthal Y, and that Neanderthals were going through the disruptive process of developing a new sex-determining gene, as some rodents have done.

Was the Neanderthal Y Chromosome Toxic in Hybrid Boys?

Another possibility is that the Neanderthal Y chromosome does not interact with genes on other chromosomes in modern humans.

The missing Neanderthal Y can then be explained by “Haldane’s rule”. In the 1920s, the British biologist JBS Haldane noted that, in hybrids between species, if one sex is sterile, rare or unhealthy, it is always the sex with unequal sex chromosomes.

In mammals and other animals where females have XX chromosomes and males have XY, it is disproportionately the male hybrids that are unfit or sterile. In birds, butterflies and other animals where males have ZZ chromosomes and females have ZW, it is the females.

Many crosses between different types of mice show this pattern, as do crosses between cats. For example, in crosses between lions and tigers (ligers and tigons), females are fertile but males are sterile.

We still lack a good explanation of Haldane’s rule. It is one of the enduring mysteries of classical genetics.

But it seems likely that the Y chromosome of one species has evolved to interact with genes from other chromosomes of its own species, rather than with genes from a related species that contain even small changes.

We know that genes on the Y chromosome evolve much faster than genes on other chromosomes. In addition, several genes have a function in the production of sperm. This could explain the infertility of male hybrids.

This could explain why the Neanderthal Y was lost. It also raises the possibility that it was the Y chromosome’s fault, by imposing a reproductive barrier, that Neanderthals and humans became separate species in the first place.

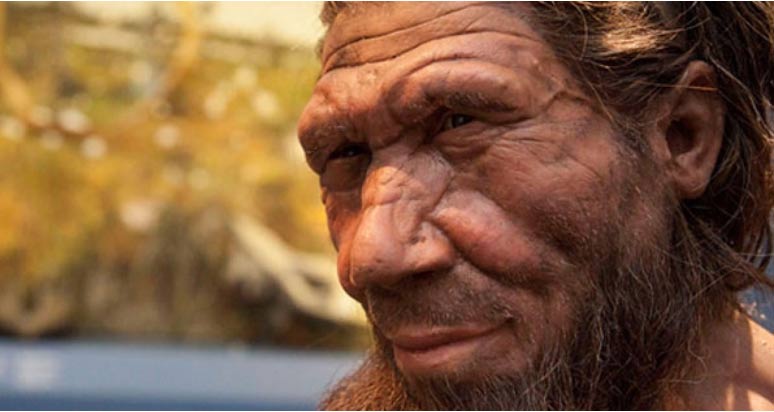

Top image: An artist’s reconstruction of a Neanderthal, on display in the exhibition ‘Britain: One Million Years of the Human Story’. Source: The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

This article was originally published under the title ‘Modern human DNA contains bits of the entire Neanderthal genome – except for the Y chromosome. What happened?‘ Through Jenny Graven on The conversationand is republished under a Creative Commons license.